Cicada

The following Cicada information will focus primarily on Magicicada. (called Magicicada septemcassini because of its 17-year lifecycle) and the upcoming emergence of Brood ll. History of the Cicada and other interesting facts are also included.

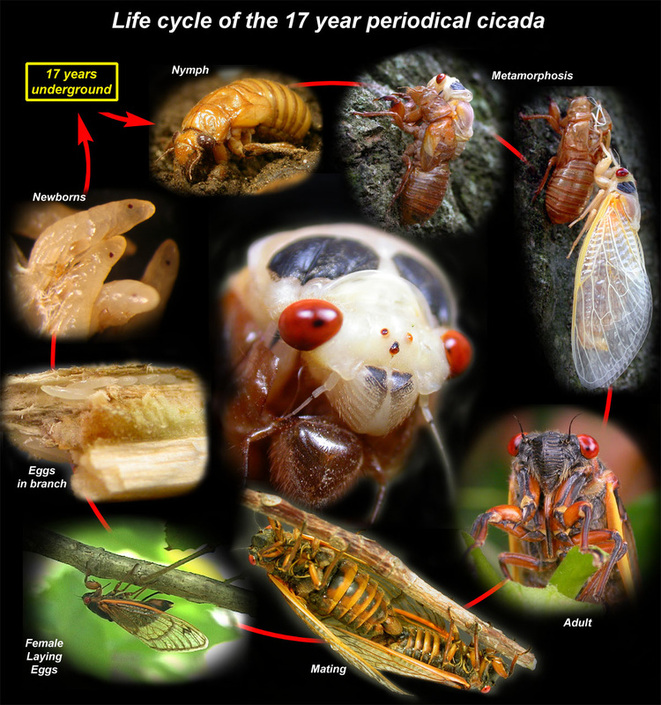

Life Cycle of the Magicicada

image Courtesy of www.fasebj.org

Periodical cicadas spend the majority of their life as nymphs underground suckling on sap from tree roots, a mere ∼1% of their lifetime is spent above ground. It is believed that a genetically determined developmental synchronization of the species is responsible for their timely exodus to the surface to reproduce. When the soil temperature exceeds 64°F (9)⇓ , the underground-dwelling nymphs emerge and attach to small plants or trees to molt their exoskeleton. Metamorphosis takes ∼1–1.5 hours to complete, and during this time the wings unfold, elongate, and harden. After a few hours, the cream-colored exoskeleton of the newly morphed cicadas turns black and hardens and the cicadas climb to the tops of tree branches to fully mature. This “teneral” adult stage lasts for a period of ∼4–6 days.

After 17 years underground, cicadas emerge en masse as nymphs and morph into flying insects. Serenading males attract females to reproduce. Once the males have attracted a female, they will mate over a period of 1 hour, whereby males clasp onto the posterior aspect of the female and introduce their sperm to fertilize the eggs. A few days after egg fertilization, the females deposit their eggs under the bark of small branches of trees using their ovipositor. While in the branch, the eggs mature over a period of 2 months and then rupture from their capsule emerging as small nymphs that then fall to the ground and rapidly burrow into the soil. These offspring begin the underground nymph stage and will emerge to mate after 17 years (Brood ll , 2013).

Cicadas have little time to complete their mating and egg laying tasks. The end of their life cycle, which is spent above ground, lasts 2 to 4 weeks.

How many kinds of Cicadas are there in the US?

There are seven species of Magicicada. The 17 year varieties: septendecim, cassini, septendecula, and the 13 year varieties: neotredecim, tredecim, tredecassini and tredecula. Each species is slightly different in coloring, song or other attributes. Cicadas are found around the world.

Whats That Sound?

Mating call of the male M. cassini consists of a series of small ticks followed by a single undulated buzz. Cicada sound is considered to be the loudest form of an insect song. Cicadas are insects under the order of Hemiptera and classified to be grouped under the suborder of Auchenorrhyncha and are collectively within the family genus of Cicadoidea. Cicada sounds are collectively produced sounds by the female and male cicadas. But mainly the cicada sound is recognized and commonly attributed to only the males.

Cicada sound is not limited to the male singing but is also classified with the female responses. A female cicada responds to the male attraction by maneuvering its wings to create flicking sounds. This process is scientifically termed as female-wing-flick. This entails rapid wing movement that creates a continuous sound. The male cicada then observes this manner and then assumes that the female displays positive attraction, the male then further enhances its sound by reacting with more of the clicking of his tymbals. This then makes a sound duet for both the female and male cicada, hence concludes the pre-mating rituals of cicadas and mates eventually.

Cicada sound is unique and are largely massive. (synchronized) A male cicada can produce a sound of about 100 decibels, thus when sung or voiced aggregately with other male cicadas, the sound then becomes deafening. Male cicadas usually gather in units and counts to over a thousand male cicadas. They sing in chorus but communally sing at a single tone and pulse. The process of cicada sounding is not limited to a stationary halt instead it mobiles itself to be singing while it flies, hovers and lands on different trees and plants.

Cicada Identification

Though Magicicadas are easy to recognize as a group, telling the individual species apart is more difficult, since they are all black with red eyes. Their songs are different and there are subtle differences in their coloration. Males of each of these 17 yr periodical species are easily identified by their characteristic mating call used to attract females. M. septendecim produces a pure tone song that resembles the word “pharaoh,” whereas the mating song of M. cassini consists of a series of ticks followed by a final buzz. M. septendecula, on the other hand, produces short chirps with each string of chirps lasting 10–30 seconds. Each of these species produce a protest call when gently perturbed.

Environmental Impact

Cicadas do not bite or sting, and They feed exclusively on tree sap.

Unlike locusts, cicadas do very little damage to their environment. Generally, the females lay their eggs on the branches of mature trees that usually appear to survive the onslaught quite well. When the eggs hatch, the larvae drop to the ground below the tree where they burrow into the ground.

In the years they live underground, the nymphs feed on sap that they drain from the tree’s roots. But they grow very slowly and so don’t have a visible impact on their hosts. There is even some evidence that the bodies of the nymphs can provide essential nutrients for tree growth in some environments.

During their underground stages, cicadas are a favorite food of shrews and moles. When they emerge, they provide a veritable feast for a number of bird species, including starlings and robins, squirrels, turtles and snakes. There are species of spiders and wasps that also like to lunch on the insects. There are even fungi that specialize in feeding on Cicada. (Courtesy of Associate Professor of Biological Sciences Patrick Abbot)

Cicadas do not bite or sting, and They feed exclusively on tree sap.

Unlike locusts, cicadas do very little damage to their environment. Generally, the females lay their eggs on the branches of mature trees that usually appear to survive the onslaught quite well. When the eggs hatch, the larvae drop to the ground below the tree where they burrow into the ground.

In the years they live underground, the nymphs feed on sap that they drain from the tree’s roots. But they grow very slowly and so don’t have a visible impact on their hosts. There is even some evidence that the bodies of the nymphs can provide essential nutrients for tree growth in some environments.

During their underground stages, cicadas are a favorite food of shrews and moles. When they emerge, they provide a veritable feast for a number of bird species, including starlings and robins, squirrels, turtles and snakes. There are species of spiders and wasps that also like to lunch on the insects. There are even fungi that specialize in feeding on Cicada. (Courtesy of Associate Professor of Biological Sciences Patrick Abbot)

Other Cicada Groups

There are 12 groups of Magicicadas with 17 year life cycles, and 3 groups of Magicicadas with 13 year life cycles. Each of these groups emerge in a specific series of years, rarely overlapping (17 year groups co-emerge every 289 years). Each of these groups emerge in the same geographic area their parents emerged. These groups, each assigned a specific Roman numeral, are called broods.

Of the 17 yr Brood X cicadas, three known species emerged in 2004. The larger M. septendecim (∼3.0 cm body length) was first to appear in May, followed in June by the smaller sized M. cassini and M. septendecula (∼2.3 cm body length). M. cassini are distinguished by their entirely black abdomen, whereas M. septendecim and M. septendecula exhibit orange stripes along the underside of each abdominal segment. In all species, strikingly bright red eyes are a hallmark feature. Other members of the Magicicada species exist in the same regions. However, these closely related species emerge on a 13 yr lifecycle (8)⇓ . In addition to the periodical cicadas, there are the annual Dogday cicadas (Tibicen canicularis) that emerge every year in July and August.

There are 12 groups of Magicicadas with 17 year life cycles, and 3 groups of Magicicadas with 13 year life cycles. Each of these groups emerge in a specific series of years, rarely overlapping (17 year groups co-emerge every 289 years). Each of these groups emerge in the same geographic area their parents emerged. These groups, each assigned a specific Roman numeral, are called broods.

Of the 17 yr Brood X cicadas, three known species emerged in 2004. The larger M. septendecim (∼3.0 cm body length) was first to appear in May, followed in June by the smaller sized M. cassini and M. septendecula (∼2.3 cm body length). M. cassini are distinguished by their entirely black abdomen, whereas M. septendecim and M. septendecula exhibit orange stripes along the underside of each abdominal segment. In all species, strikingly bright red eyes are a hallmark feature. Other members of the Magicicada species exist in the same regions. However, these closely related species emerge on a 13 yr lifecycle (8)⇓ . In addition to the periodical cicadas, there are the annual Dogday cicadas (Tibicen canicularis) that emerge every year in July and August.

Cicadas in History and Lore

Artifacts from the Pacific Northwest reveal that some tribes of Native Americans considered the Cicada a sacred object, and ate them during ceremonial gatherings. The Oraibi Indians of Arizona, according also thought that the cicada’s life cycle symbolized resurrection.

Anthropologists believe that many indigenous tribes from the Americas to Africa, "mimicked" the rhythm and sound of the Cicada in their songs and chants with rattles, wood rakes and other crude musical instruments.

Cicadas are found in most places around the world. Areas with long established cultures like China, considered the Cicada as a symbol of rebirth and life after death. Images of Cicadas have been found on numerous artifacts in Asia. The earliest were found on deer antlers at An-Yang, China, dated 1766 BC.

During the Han Dynasty, Jade carvings of Cicadas were placed on the tongue of deceased persons apparently to induce resurrection. It is interesting to note, that the same symbol of the Cicada, carved in jade, was used by the Mayas of Mexico on the opposite side of the world.

The ancient Greeks believed that Cicadas were originally humans who, in ancient times, allowed the first Muses to enchant them into singing and dancing so long that they stopped eating and sleeping and actually died without noticing it. The Muses rewarded them with the gift of never needing food or sleep, but to sing from birth to death. The task of the Cicadas is to watch humans and report who honors the Muses and who does not.

Artifacts from the Pacific Northwest reveal that some tribes of Native Americans considered the Cicada a sacred object, and ate them during ceremonial gatherings. The Oraibi Indians of Arizona, according also thought that the cicada’s life cycle symbolized resurrection.

Anthropologists believe that many indigenous tribes from the Americas to Africa, "mimicked" the rhythm and sound of the Cicada in their songs and chants with rattles, wood rakes and other crude musical instruments.

Cicadas are found in most places around the world. Areas with long established cultures like China, considered the Cicada as a symbol of rebirth and life after death. Images of Cicadas have been found on numerous artifacts in Asia. The earliest were found on deer antlers at An-Yang, China, dated 1766 BC.

During the Han Dynasty, Jade carvings of Cicadas were placed on the tongue of deceased persons apparently to induce resurrection. It is interesting to note, that the same symbol of the Cicada, carved in jade, was used by the Mayas of Mexico on the opposite side of the world.

The ancient Greeks believed that Cicadas were originally humans who, in ancient times, allowed the first Muses to enchant them into singing and dancing so long that they stopped eating and sleeping and actually died without noticing it. The Muses rewarded them with the gift of never needing food or sleep, but to sing from birth to death. The task of the Cicadas is to watch humans and report who honors the Muses and who does not.

Other Cicada Facts

Cicadas are still consumed as food around the world, in all stages of life. Larve, Nymph, Grub and Adult. They are known in history to have been eaten in Ancient Greece as well as China, Malaysia, Burma, Latin America, and the Congo. Female cicadas are prized for being meatier. Shells of cicadas are employed in the traditional medicines of China.

In the famous video games series Pokemon, three Pokemon are based on cicadas, one representing the underground larva, another the adult insect and the other symbolizing the empty skin after molting.

In the famous video games series Pokemon, three Pokemon are based on cicadas, one representing the underground larva, another the adult insect and the other symbolizing the empty skin after molting.

The Science of Cicada Sound

Male cicadas produce mating calls by oscillating a pair of superfast tymbal muscles in their anterior abdominal cavity that pull on and buckle stiff-ribbed cuticular tymbal membranes located beneath the folded wings. The functional anatomy and rattling of the tymbal organ in 17 yr periodical cicada, Magicicada cassini (Brood X), were revealed by high-resolution microcomputed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, electron microscopy, and laser vibrometry to understand the mechanism of sound production in these insects. Each 50 Hz muscle contraction yielded five to six stages of rib buckling in the tymbal, and a small release of muscle tension resulted in a rapid recovery due to the spring-loaded nature of the stiff ribs in the resilin-rich tymbal. The tymbal muscle sarcomeres have thick and thin filaments that are 30% shorter than those in flight muscles, with Z-bands that were thicker and configured into novel perforated hexagonal lattices. Caffeine-treated fibers supercontracted by allowing thick filaments to traverse the Z-band through its open lattice. This superfast sonic muscle illustrates design features, especially the matching hexagonal symmetry of the myofilaments and the perforated Z-band that contribute to high-speed contractions, long endurance, and potentially supercontraction needed for producing enduring mating songs and choruses.

Superfast striated muscles are found in sound-producing organs throughout nature, including the tailshaker muscle of the rattlesnake, the swimbladder muscle of toadfish and the tymbal muscle of cicadas. Known as “sonic” muscles, they typically operate at frequencies above 50 times per second, rates that are 2- to 3-fold of those that can be attained by typical skeletal muscle. Most sonic muscles are synchronous (or neurogenic) whereby each nerve impulse triggers one muscle contraction. This is in contrast to other high frequency muscles such as some insect flight muscles that are asynchronous (myogenic), and in this situation each nerve impulse produces multiple stretch-activated contractions that are propagated by the antagonistic movement of the thorax and the wings.

Synchronous superfast muscles frequently incorporate speed-enhancing organization that allows ample ATP production and delivery, fast calcium triggering, and rapid relaxation, along with efficient force transmission. Here we present insights from the tymbal muscle of the male periodical cicada, Magicicada cassini (brood X), as billions of these insects emerged in 2004 to pay their once-in-17-year visit above ground to mate in the northeast and midwest United States. We have explored the functional anatomy of this muscle by state-of-the-art multimodal imaging and examined the structural and functional properties on how it produces the incessant mating sound by vibrating the tymbals and resonating sound in the body cavity. We observed that myofilament structure is specifically adapted for high speed and endurance in cicada tymbal muscle.

Male cicadas produce mating calls by oscillating a pair of superfast tymbal muscles in their anterior abdominal cavity that pull on and buckle stiff-ribbed cuticular tymbal membranes located beneath the folded wings. The functional anatomy and rattling of the tymbal organ in 17 yr periodical cicada, Magicicada cassini (Brood X), were revealed by high-resolution microcomputed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, electron microscopy, and laser vibrometry to understand the mechanism of sound production in these insects. Each 50 Hz muscle contraction yielded five to six stages of rib buckling in the tymbal, and a small release of muscle tension resulted in a rapid recovery due to the spring-loaded nature of the stiff ribs in the resilin-rich tymbal. The tymbal muscle sarcomeres have thick and thin filaments that are 30% shorter than those in flight muscles, with Z-bands that were thicker and configured into novel perforated hexagonal lattices. Caffeine-treated fibers supercontracted by allowing thick filaments to traverse the Z-band through its open lattice. This superfast sonic muscle illustrates design features, especially the matching hexagonal symmetry of the myofilaments and the perforated Z-band that contribute to high-speed contractions, long endurance, and potentially supercontraction needed for producing enduring mating songs and choruses.

Superfast striated muscles are found in sound-producing organs throughout nature, including the tailshaker muscle of the rattlesnake, the swimbladder muscle of toadfish and the tymbal muscle of cicadas. Known as “sonic” muscles, they typically operate at frequencies above 50 times per second, rates that are 2- to 3-fold of those that can be attained by typical skeletal muscle. Most sonic muscles are synchronous (or neurogenic) whereby each nerve impulse triggers one muscle contraction. This is in contrast to other high frequency muscles such as some insect flight muscles that are asynchronous (myogenic), and in this situation each nerve impulse produces multiple stretch-activated contractions that are propagated by the antagonistic movement of the thorax and the wings.

Synchronous superfast muscles frequently incorporate speed-enhancing organization that allows ample ATP production and delivery, fast calcium triggering, and rapid relaxation, along with efficient force transmission. Here we present insights from the tymbal muscle of the male periodical cicada, Magicicada cassini (brood X), as billions of these insects emerged in 2004 to pay their once-in-17-year visit above ground to mate in the northeast and midwest United States. We have explored the functional anatomy of this muscle by state-of-the-art multimodal imaging and examined the structural and functional properties on how it produces the incessant mating sound by vibrating the tymbals and resonating sound in the body cavity. We observed that myofilament structure is specifically adapted for high speed and endurance in cicada tymbal muscle.

The following are recordings of Cicada sounds. We have also included links to numerous other recordings of Cicadas mating calls.

This LINK provides access to numerous Cicada Sounds collected by researchers at the University of Connecticut.

About Us

|

Down on the Farm

|

Find It!

|

Web Design

|